To build trust in your AI transformation, play the long game

“AI-powered” messages aren’t landing. Building trust requires nuance.

It feels like, or perhaps I optimistically hope that, we’re hitting peak hype in marketing AI.

Tech marketers live in a fever dream where AI is the sweet nectar for bees getting drunk on AI-powered wine curation to accompany a smart AI-cooked pizza, while their little one plays with a Barbie Doll powered by AI in a real-life Black Mirror episode (the one where Miley Cyrus’s soul gets trapped in a robot doll).

The assumption that your customers will seamlessly associate AI with your technological prowess is flawed.

Let’s take a step back to establish why trust in tech innovation can fail, and how you can keep it on track through better-planned communications and tech solutions that help deliver on transparency.

The trust gap is real and measurable

According to the 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer, a brilliant annual global snapshot of sentiment and trust in institutions and trends, the scales are evenly balanced: about one-third of people are positive, one-third neutral and one-third negative about willing AI into their lives.

But there are huge demographic variances. One factor is geographic. The ‘Global North’ (Europe, North America and advanced economies) are bigger cynics compared to ‘Global South’ (particularly emerging economies like China and India), who are more likely to be AI optimists. It’s more of a gulf than a gap. In China, 72% of people place their trust in AI. In the US, it drops to 32%.

The AI trust divide has multiple parameters: older people, those with lower incomes, and women are less likely to trust AI.

Why this disparity? Perhaps those with the most to gain, like nations in growth mode with younger populations, feel more opportunity than threat compared with established economies that have more to lose from technological disruption. Emerging economies have been net beneficiaries from globalisation in recent years and may not yet have experienced the sting of technology or offshoring displacing roles, and pulling down entire communities with it.

In sub-Saharan Africa, digital transformation had a different shape, where fixed-line phones and broadband (and in some areas, access to reliable electricity) are less commonplace. Mobile banking and digital currencies have leapfrogged over the previous computer-based transformation in most developed nations. AI could take a similar fast track.

Automation fails to live up to the promise

To trust technology, we need to see it improve everyday life for us first-hand.

Take pricing. We're used to seeing fluctuating rates for experiences and services. Like that late-night sofa browse for flights, then prices seem to creep up the moment you go to book.

But how would you feel if the airline started hyping the merits of its "AI-powered price recommendations" but failed to explain why it benefits you that the price of the same seat on the same flight swoops up and down like gulls spying a bag of chips on the beach?

Or worse, you start to suspect that the more you check your flight price, the more it goes up. This is a known problem, as algorithms equate search with demand and ratchet up accordingly.

In the real world, we've all experienced seriously weakened services, often synonymous with automation and AI. Like the McDonald's recruiter bot that was more likely to serve up a soggy cheeseburger of exposed applicants' personal data than help entry-level job seekers to have a nice day.

I recently had money stolen (I can use no euphemism, theft it was pure and simple) by Uber Eats, who refused to accept that a mistaken order cancelled within seconds was a genuine error due to its flawed app design. No ability to escalate or provide evidence (including calling the restaurant to confirm the cancellation) would wash. It appears Uber employs no humans at all in their food order process. Talk about trimming the fat. They’ve taken customer service down to the bone.

Giving your customer no opportunity for a right to reply, and no human in the loop, should not meet EU AI Act regulations. But like the Lamborghini driver cruising the high street, we presume big tech with big pockets has factored in costs to occasionally pony up to pay trivial fines.

Automation promises efficiency for all, but frequently underserves those whom society already serves least. Those furthest from the white Silicon Valley archetype are typically the worst served by AI: women, older workers, and non-native English speakers are more likely to experience bias or weaker services, from poor voice recognition to reduced access to credit.

We need to double down to give them more reasons to trust your tech.

“It’s all our fault”

Science fiction has been far more accurate at tech predictions than futurists or economists.

Writer Russell T. Davies, usually producing family-friendly sci-fi Dr Who, wrote a frighteningly prophetic British BBC drama that sticks with you. More so than tales of Daleks and Cybermen, Years and Years had me hiding in fear behind the sofa.

Broadcast in 2019, it’s set in a near-future Britain where things unravel rapidly with the advent of new technologies and the Overton window shifting to the right.

In 2024, Queen Elizabeth dies, Trump wins a second term and global instability mounts. The family breadwinners lose their jobs to AI. A teenager comes out as ‘transhuman’ and has a brain chip installed. A character dying from radiation exposure following a US nuclear attack on China has her consciousness uploaded to the cloud. Asylum seekers are imprisoned in death camps, using advanced satellites to hide them from surveillance. But on the up, phones have a brilliant battery life.

The technology trends were expertly researched and plausible. But it couldn’t happen here, could it?, I mused from the comfort of my sofa.

The impact of automation on daily life is a recurring theme. The series definitive speech comes from family matriarch, grandmother Muriel (performed by the formidable Anne Reid) on the consequences of standing on the sidelines when technology moves at a pace faster than we can adapt.

“I saw it all going wrong 20 years ago in the supermarkets when they replaced all the women on the till with automated checkouts. Did you walk out? Did you write letters of complaint?

No.

You huffed and you puffed and you put up with it. And now all those women are gone. And we let it happen. It’s all our fault. This is the world we built.”

Personalisation and automation promise shrink-wrapped hyperspeed convenience, yet technology is often weakening our interaction with organisations.

Privacy advocate Cory Doctorow coined the term "enshittification" in 2022 to describe how digital services degrade as the goal shifts from delighting users to maximising shareholder profit. The concept stuck like the proverbial to the wall. It became the American Dialect Society’s 2023 Word of the Year.

"We're all living through the enshittocene, a great enshittening, in which the services that matter to us, that we rely on, are turning into giant piles of shit. It's frustrating. It's demoralising. It's even terrifying."

For a live example, log in to Facebook today and enjoy the stream of adverts, nostalgia and angry rants, with friends' births, deaths and marriages swimming in the alarmist AI-slop. Meta seems to be maintaining this legacy platform as an elaborate tool to analyse your behaviour to sell your data for dimes to advertisers.

For product owners, automation is fool’s gold. It glitters and promises the enterprise the same or more for less, but poor execution (often linked to badly managed data) and the randomness of pesky customers mean there’s a frequent mismatch between the organisation’s intent to serve and what customers receive.

This can lead to japsters working out how to order 18,000 cups of water from an AI-bot at Taco Bell (presumably to quench this notoriously energy-thirsty tech). Or a “personalisation dissonance” as too many automated messages, crafted for different purposes without a consistent ethos or tone of voice, make those in receipt feel unheard and irritated.

It is, after all, far easier to send one million unsolicited emails than read them all.

Don’t assume the marketing recipient or service user will respect the time we’ve made to make everything work like clockwork. If they don’t like it, they’ll ignore it. Or try to break it.

As services weaken, so does consumer trust. We’re always one soggy burger away from an account deletion. Even with market dominance, as Facebook and X (Twitter) are discovering, there’s always a different way to get to the same outcome by using a competitor or living without your services.

Lead with outcomes, not technology

As communicators, we need to understand how trust impacts reputation. If your primary customer base is US women over 50 in rural and small towns, assuming they'll embrace your "AI-powered" pizza oven is a recipe for disaster. That’s not to say the product wouldn’t be a great fit – but you need to sell the sizzle, not the sausage (or pepperoni).

We need to explain what the tech does for them. Here, the angle could be that this new thermostat technology can act like an experienced chef to see exactly when the pizza is ready without needing to open the door and mess up the air circulation, so you get a perfectly cooked pizza every time.

Lead with "AI-powered" and you're asking people to trust the technology before you've demonstrated value. For those less enthused or on the fence about AI, this may trigger curiosity at best, or apathy or resistance at worst.

There are two challenges to solve:

Problem 1: You don't know how enthused your target audience is about AI

Unless you're selling a product with AI at its core, assumption is speculation. Add relevant questions to your customer panels and market research.

Problem 2: You don't know what your audience thinks you mean when you talk about AI

What people understand AI to be varies hugely. Some equate it with negative headlines: biased algorithms, job displacement, privacy threats. Parents may associate it with ChatGPT's "homework machine", dumbing down education and stripping their children of work opportunities. Enthused adopters may spark up with talk about new possibilities.

By now, all our potential customers have heard of AI. When I’ve talked in schools about my wibbly-wobbly tech career journey, I’ve asked the younger children if they knew what AI was. They all did. The 8- and 9-year-olds responded “robot”. I pressed to ask if a phone could be AI. They, and the older ones, would say yes and start to equate AI with something more like an activity served up from a device – a metal Mickey or the latest Apple watch.

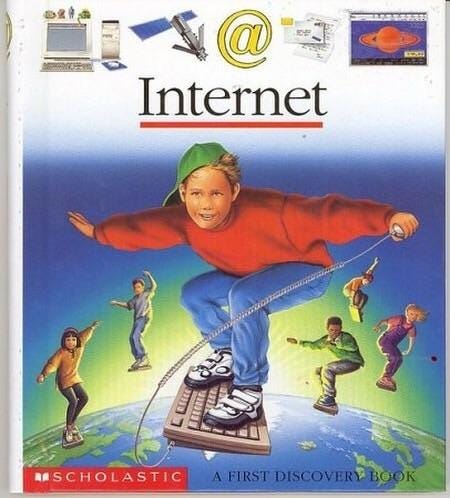

Some of the language around AI marketing takes me back to the early internet days, when I started my career building websites and ‘new media’ campaigns. “Surfing the web” was a slightly more sexy way of describing using the internet. The early web users were researchers, academics and ‘tech geeks’. Telecoms firms needed to make uptake feel accessible to all to bag those monthly dial-up charges.

The brave new technological future was promoted with things like this:

By around 2002, “surfing the web” was a cringe expression only said by your granddad after he’d signed up for an AOL subscription from the free CD-ROM sent in the post.

By the mid-noughties, using the internet was what we did at home, work and college because it benefited us. Hype had shifted to utility and usefulness.

Today’s “AI-powered” message could become tomorrow’s bad ad cliché.

While writing this, I saw a YouTube advert for Revolt, a challenger consumer digital bank, hyping its AI-powered services. I have no idea what they meant, and the skippable ad format didn’t lend itself to a nuanced discussion. You don’t choose your bank because they use AI (doesn’t everyone?). You choose them for reliability, services and value.

Smart marketers switch off the hype button. They lead with outcomes, not technology.

They don't talk about "AI-powered customer service".

They explain how the technology offers "instant, comprehensive answers to your questions."

They avoid "AI-driven recruitment tools".

They promise "fairer, more detailed candidate evaluation."

Instead of "machine learning analytics," they talk about "insights that help you make better decisions."

The exact technology isn't the end goal; it's the means to the end. It’s the end improvement in the product, service or experience that counts.

Making AI explainable without a lab coat

Customers don't need to understand how neural networks work, but they do need to understand how AI impacts them. Making AI explainable isn't about technical education, it builds understanding to improve trust.

How to explain complex technology well depends on what you do and your audience’s preferences. Burying reports or statements within your annual reports or news section of your website won’t wash.

For customer explanations, answer these questions as simply as you can:

What is the AI doing?

Don't say "AI analyses your data." Explain what exactly: "Our technology compares your mobile usage patterns with similar customers to suggest a contract that could save you money."

How does this benefit me?

Generic efficiency claims fall flat. Be specific: "Our booking technology schedules deliveries for when you're most likely to be home."

How will my data be used?

Explain data usage, collection, storage and deletion in plain English. "We ask for your postcode so we can recommend events at your nearest store." Link to your data privacy, AI and cybersecurity policies.

How to do transparency well

Some leading organisations, particularly those operating in high-tech spaces or with global operations, have created AI transparency centres. These are online or physical spaces where business customers (primarily) can explore technology in detail by accessing reports, conducting code reviews or challenging AI decisions with human oversight.

For customer-facing comms, steal from big tech's playbook. Netflix explains how its recommendation engine works. Spotify explains how to improve the relevancy of your Discover Weekly playlist. And Amazon explains how a new AI solution, Features, creates personalised shopping lists.

All organisations should have a public-facing AI policy that explains in plain English its intentions for using AI in the delivery of products and services, and what customers should expect. UK broadcaster Channel 4’s AI Principles is a good template for explaining in simple terms its intention and outcomes.

“At Channel 4, we believe AI is here to support human creativity, not replace it. So we’re not handing the keys to the machines.”

I like the way it explains its goal of AI to trim down the mundane, and where the limitations will be so its reputation for world-class creative broadcasting will not be compromised. Its positive intent creates momentum with measurable and clear goals.

Your policy can be a starting point for exploring more audience-friendly content formats like educational explainer videos, infographics or podcasts that unpack the technology story in more detail, particularly for specialist B2B audiences.

Building internal AI literacy

As well as your customers, you need to consider how you will educate your teams to make sure AI-led services are properly understood and risk managed accordingly.

The EU AI Act's literacy requirements challenge organisations to do more than just show employees how your tools work. AI literacy is defined as:

"The skills, knowledge and understanding required to facilitate informed deployment of AI systems and gain awareness of opportunities, risks, and possible harm."

Effective AI literacy addresses technical understanding (how tools work), risk awareness (recognising anomalous or harmful outputs) and ethics (who might be affected and what safeguards you will put in place).

This isn't one-size-fits-all training. The Dutch supervisory authority notes that the training needs must fit the context of how the system is used and how users may be affected.

The goal isn't to turn everyone into AI experts. It's to build informed confidence to make better decisions about when and how to use AI tools – and when to turn them off.

Getting tech transformation right is incredibly difficult. Honest communication about how you’re handling it builds trust more firmly than hype or overpromising. Sharing lessons from success and failures, and explaining what you will do to improve it, can earn more confidence than CEOs who shout about “AI-first”. In some cases, like Klarna, which rolled back its AI customer agent programme, a more measured transformation can avoid expensive and reputationally damaging U-turns and a public serving of humble pie.

Neurosymbolic AI – a path to trusted AI?

In addition to communications, there are technology solutions that can enhance trust in machine learning systems. One of the most promising is neurosymbolic AI, which combines pattern recognition with rules to make AI explainable.

Traditional neural networks are often referred to as “black boxes”. They process inputs and produce outputs. But these autonomous systems are designed to optimise based on the best results, so the reasoning becomes opaque.

Symbolic systems use defined rules and logic that can be examined and understood, but they struggle with ambiguous or novel situations. So they could freak out if a customer adds text or speaks in a way that doesn’t appear in its training data.

Neurosymbolic AI combines the best of both: using neural networks’ superpower to identify patterns and opportunities, and symbolic components to apply business rules, ethical constraints and logical reasoning.

A loan approval system using neurosymbolic AI could use neural networks to identify risk patterns in applicant data, then apply symbolic reasoning to ensure decisions follow fair lending principles and comply with regulations.

Users can understand not just what the AI decided, but why it made that choice and how business rules and ethical constraints shaped the outcome.

How to start building trust in AI

Building trust isn't about swapping "digital transformation" for "AI-powered" in your marketing; it needs a systematic approach that includes a layer of technology for digital trust, and a communication strand to make it transparent and explainable to your stakeholders – be they technical partners, members of the public or end users.

There is much to do. Let’s begin.

Start with stakeholder mapping

Identify who needs to trust your AI systems (e.g. customers, employees, regulators, partners) and map out, from direct conversations (e.g. customer panels) or indirect (e.g. social listening reports), their concerns and what they want to know. Strategies that work for tech-savvy Gen Z may backfire with sceptical older customers. But don’t assume, ask.

Design for transparency

Don't treat AI explainability as something you’ll do later once you get the system to work as intended. AI systems designed with transparency in mind perform better and gain adoption faster. Set out your stall with outward initiatives like your public-facing AI policies, while you work on more detailed systems and communication methods like transparency reports or a transparency centre.

Create informal feedback loops

Establish mechanisms for users to report problems in situ, suggest improvements and see how their input shapes technology development. It’s not the same as a bug bounty programme, but more about iterative user testing and suggestions. Trust grows when people feel heard and see how you’re responding.

Invest in human oversight

AI systems must include human review processes (“the human in the loop”) with a push button or options to appeal or override if the user feels unsafe. Waymo autonomous taxis must have a ‘help’ button for safety. Because accidents can and will happen, and some of us have seen or read Stephen King’s Christine.

It may seem inefficient to build end-to-end automation, then have to add people back in. But without the ‘help’ button, your users may feel unsafe, and ultimately opt for ‘eject’ next time they want to buy again or their contract is up for renewal.

Measure interest alongside uptake

Like the supermarket self-checkout users, uptake isn’t the same as acceptance. Survey users about their comfort level with interacting with AI or knowing AI is used in the delivery of your services. Find out, in their own words, their understanding of how your systems work and their confidence in using them.

Be honest about limitations

No organisation has infinite resources to build technology or support every edge case customer need. Responsible AI is a technical and business process that’s a ‘work in progress’ – you don’t know how automation systems work until they’re in the wild.

Data can ‘drift’, like a fraud modelling system that breaks when fraudsters adopt a new platform or trend that wasn’t in the original training data. Explain how you will keep your engines tuned up and deal with errors (or disgruntled recipients of the soggy burger).

Trust is a long game

The pressure to roll out tech solutions before your competitors is real. But those who launch in haste may repent at leisure.

A rough and ready initial rollout might work for new brands delivering non-essential services, but it's riskier for established organisations like a bank whose customers aren't bothered about AI but do want to be able to access their money easily 24/7.

Trust in technology isn't achieved through press releases or marketing spin. It's earned through hard graft: ongoing conversations about what you’re doing and how it’s working to show your tech is improving things for your user. And if it isn’t, let them help you shape a better product.

What success stories can you share with me about how you’ve won over sceptics to build trust in AI? This post is free to read and share.